Waiters

Waiters and Cooks as Underground Railroad Agents in Niagara Falls

Tourists from all over the U.S., Canada, and Europe came to Niagara Falls to see its spectacular waterfalls. They supported a huge tourism economy, expanding the population of the village from 1401 year-round residents in 1840 to more than 50,000 visitors who came from May through October by the 1850s.

Woven into this tide of sightseers were refugees from slavery. They came not to see the sites but because Niagara Falls offered the narrowest crossing point the river from slavery in the U.S. to freedom in Canada.

Before the American Civil War, the Cataract House was one of the largest single employers of people of African ancestry in the United States and Canada. Hotel workers of African descent made the Cataract House a major center of Underground Railroad activity.

Before the American Civil War, the Cataract House was one of the largest single employers of people of African ancestry in the United States and Canada. Hotel workers of African descent made the Cataract House a major center of Underground Railroad activity.

From the 1830s on, almost the entire wait staff, several cooks, and many porters were African-descended people. The number expanded by 1840 to twenty, to twenty-eight in 1850 (out of a population of forty-four people of African descent in Niagara Falls, New York), to sixty in 1860 (there was a total of 244 people of African descent living in Niagara Falls).

The Cataract House was open from May to October each years. Offering only seasonal employment as a result, the hotel had an an ever-changing kaleidoscope of employees. Based on place of birth in a Southern state, Canada, or else listed as of “unknown” origins in the US census as many as 80 percent of these employees may have been once enslaved. In Niagara Falls, they risked their own liberty in efforts to assist freedom seekers on their way to Canada.

Cataract waiters set the standard for elegant dining. They also worked as undercover agents for the Underground Railroad, endangering their own freedom by rowing refugees cross the river in small boats. These were anchored at the base of the Falls on the US side. This was part of an Underground Railroad network that included crossing points at the Suspension Bridge. The great bridge was built between 1848-1856 two miles north of the Cataract House. Other popular transit points included Buffalo, Lewiston, and Youngstown. The Cataract house waiters worked with other local agents, including families of African descent and a few white families.

This network of antislavery-minded activists reached into far into the South as well as across the border into Canada. Most hotel employees lived with their families in the off-season in towns and cities scattered throughout the borderland on either side of the Niagara River. By far the majority had been born in the United States. Some lived on the U.S. side of the Niagara River in Rochester, Geneva, or Lockport, New York. Many, however, were African Canadians, with homes and families in Toronto, Brantford, Hamilton and other locations in Upper Canada/Canada West.

These waiters were also supported by entrepreneurial families of color in Niagara Falls who had begun their careers at the Cataract House. Some of them later opened local tourism businesses of their own, including a hotel, employment agency, restaurant, photography shop, and a stand for making and selling beadwork.

Waiters and Work

At least by 1830, Cataract House owner Parkhurst Whitney began to employ men of African descent as waiters. Four men of color worked at the Cataract House in 1830, twenty were employed there in 1840, twenty-eight (including two women) lived and worked in the Cataract House in 1850. By 1860, sixty African Americans both resided in and were employed at the Cataract House, including six female servants and Catherine Polk, cook. Fifty-one male waiters of African descent also were employed by the International Hotel.

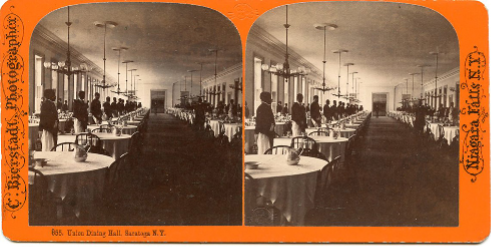

Cataract House Dining Room, 1898

Courtesy Niagara Falls (N.Y.) Public Library

By 1850, a core group of African American and African Canadian men and a few women returned to work at the Cataract House year after year, through the time of the American Civil War. These people were employed as waiters, cooks, chambermaids and porters, along with a few entrepreneurs who had their own business ventures in Niagara Falls, New York.

They also carried out undercover work on the Underground Railroad. Among these were John W. Morrison, James and Luvisa Patterson, Lewis H.F. Hamilton and Clarissa Condol Hamilton, Catherine Polk, Madison Freeman, William Bell Fossett and Dorothy Condol Fossett, John Murphy, Moseby Hubbard, and John A. Bolden. Some of these individuals had almost certainly been once enslaved themselves, as suggested by the place of birth they listed in the US census, and some in the Canadian.

Under the direction of the head waiter John Morrison, waiters at the Cataract House were well-trained and professional, working with military precision to serve guests from around the world. In 1848, Tunis Campbell, a waiter who worked at the Howard Hotel in New York City, published Hotel Keepers, Head Waiters, and Housekeepers' Guide (Boston: Coolidge and Wilsey, 1848). It outlined in detail how to train waiters to undertake organized and precise maneuvers, serving each dish in unison with one another, in time to the beat of a drum. "Waiting-men,” he directed, “should be drilled every day, except Saturday and Sunday. Saturday should be used as a general cleaning day; and Sunday we should, if possible, go to church." Managers should treat their staff with respect.

Primary Sources:

1. Waiters and Work: Written descriptions.

Visitors to the Cataract House often described the work of the waiters as part of what made their visit a memorable experience. These three visitors left a record of their experiences in 1844-45, before Tunis Campbell had published his manual. This suggests the possibility that waiters at the Cataract House became one of the models for Campbell’s book.

a. Miss Leslie, “Niagara,” Godey’s Ladies Book (December 1845),

I must in justice mention that we were excellently accommodated at the Cataract House, a large, elegant, and well kept establishment, with handsome drawing-rooms, comfortable chambers, efficient servants, and a table not inferior to those of the chief hotels in the Atlantic cities.

The waiters were very numerous, and of every shade of what, in their case, is denominated colour; black, brown, and yellow; and one or two were copper-tinted and Indian-featured. They were all dressed alike, in clean white jackets and trowsers; but their style of hair displayed a pleasing variety.

It was amusing to see the manner in which this troop of well-drilled domestics brought in the dessert, and placed it on the table; or rather the tables, as there were two very long ones, and a set of waiters for each. At a signal from the major-domo (who was stationed at the upper end of the room between the tables) the waiters took up the line of march in Indian file, and proceeded round with military precision, military step, and military faces. They were armed with japan trays or servers; each holding a different article. One man carried all the dessert plates, which as he passed along, he deposited in their places, slapping them down "with an air." A second had all the knives; a third the forks; a fourth the spoons, each article being put down with an air. Then came the pie-man; then the pudding-man; next the pudding-sauce man; then he of the calves-foot jelly; and he of the blanc-mange; and he of the ice cream - this last being the most popular. There were also some who had been detailed on the almond and raisin and motto secret service. Pine-apple and other fruit men brought up the rear. In this manner the whole dessert was placed on the tables in a very few minutes, and in the most complete order.1

b. Frederick Von Raumer, America and the American People (New York: J. & H. G. Langley, 1844), 456.

In the hotel six long tables were set, full of guests, and served by thirty-six black waiters, among whom the division of labor was carried so far, that each had his department—of bread, knives and forks, spoons, &c.—assigned to him. These solo performers marched with regular steps to villainous table-music, and did all their work in measured time. Thus they came, thus they went; and thus each brought in his hand two dishes, which he deposited on the table as directed by two musical fermate.

c. “Ramblings—No. 5,” 1845. Scrapbook, Niagara Falls (N.Y.) Public Library

Although this article is not signed, it was likely written by a clergyman, since he notes that he talked to “a congregation of the faithful” with “words of life and salvation.”

Niagara Falls,

Tuesday, Aug.19, 1845

Dear Reader,--We arrived at the Falls, from Buffalo, Sunday morning, in season to address a congregation of the faithful who assembled, morning and afternoon, to listen to the words of life and salvation.

The village at the Falls contains some seven or eight hundred permanent residents, and during the warm seasons is a favorite resort for visitors, of whom the number is said to be 50,000 annually, and by whom the several public houses are continually thronged. The most extensive among these houses is the “Cataract House” kept by Gen. Whitney. The house is made famous by the exactness of the manner in which the table servants wait upon visitors while they are taking their meals. They are all colored men, and number about thirty. They are so drilled by the head waiter that in removing the various dishes and replacing them, or in clearing the table and re-setting it for the dessert, they observe a perfect conformity of procedure and an exact precision of movement. Their step, the motions of their [illegible], together with all their movements, are simultaneous and regular. The several dishes strike the tables as exactly at the same instant as in a well-drilled company the muskets do the ground at the command, “ORDER ARMS.” The whole plan is “a la militaire.”

2. Waiters and Work: Images.

a.

Waiter, Unknown location, n.d. Found by Ally Spongr DeGon. This is one of the few images of a hotel waiter of African descent in the nineteenth century. This may or may not have been taken in the dining room of the Cataract House. His dress is formal, with a bow tie and leather shoes. He holds a tray over his shoulder and looks directly at the camera, confident in his work.

b. Tunis Campbell, Hotel Keepers, Head Waiters, and Housekeepers' Guide

(Boston: Coolidge and Wilsey, 1848). (Job description for steward, pp. 50-51. Dress, 31).

Before the Civil War, Tunis Campbell took advantage of the growing urban hotel trade. Catering both to business customers and tourists, he developed a highly-trained professional workforce of waiters. His 1848 book was one of the earliest hospitality manuals in the country, used by head waiters everywhere. Under John W. Morrison, waiters at the Cataract House followed this model, although it may well have been in place there before Campbell’s book was published. Campbell led a remarkable life as an abolitionist, military governor of the Georgia Sea Islands during the Civil War, and minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. After the Civil War, he became a Georgia State Senator, risking his life to defend the rights of people of color. His 1877 book, Sufferings of the Reverend T.G. Campbell and His Family in Georgia, describes his imprisonment and near death at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan.

c. Charles Bierstadt, "Grand Union Dining Hall, Saratoga." The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1870. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e1-596d-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

German-born Charles Bierstadt became a well-known photographer, an expert in stereoscopic images. Viewed through a lens, these two images merged into one three-dimensional photograph. Bierstadt, brother of the painter Albert Bierstadt, moved to Niagara Falls in 1863, where he set up a shop that sold his images to tourists from around the world.

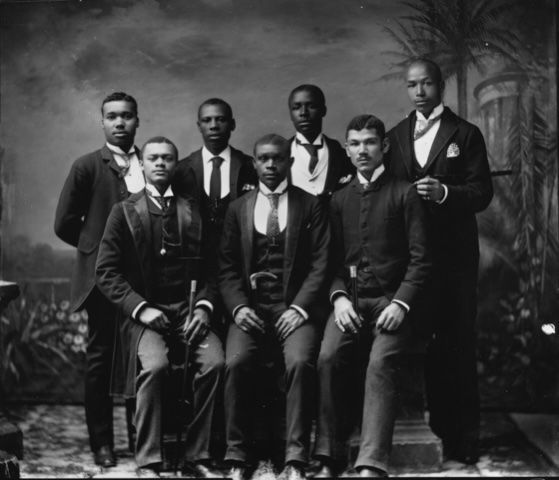

d.

Central Hotel Staff, c. 1890. Smith and Telfer Collection, Fenimore Art Museum, New York State Historical Association, Cooperstown, New York. This is one of the few known photographs of hotel waiters in the nineteenth century. These well-dressed men worked at the Central Hotel in Cooperstown, New York.

3. Waiters and Work: 1850 U.S. Census.

The Underground Railroad was a network of people across the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, incorporating refugees from slavery in the southern U.S. before the Civil War (1861-65) and those who helped them.

Because this movement was often secret, many people think that we cannot ever know how it really operated. Sometimes, this was true. In other places, however, public records offer a clue about who escaped on the Underground Railroad and the means by which they succeeded in their quest for freedom.

Census records from the U.S., Canada, and New York State are a key source. The U.S. took a census every ten years, from 1790 to the present. Although there were scattered censuses listing heads of households starting in Quebec in 1666, from 1851 on, the colonies that made up Canada took an overall census. Although data varied in each census year, usually the data collected included each member of the household, ages, occupation, religion, literacy level, ethnicity, the type of home they occupied and other details every ten years. New York State took a similar census every ten years, beginning in 1855. By 1850, U.S.s census takers were directed to record the name of every resident, including details about their ages, race/ethnicity, places of birth, occupations, home ownership, and more.

Here are two pages from the U.S. census, listing people who lived at the Cataract House in Niagara Falls on September 6, 1850.

Ancestry.com. 1850 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009. Images reproduced by FamilySearch.

Seventh Census of the United States, 1850; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, 1009 rolls); Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29; National Archives, Washington, D.C.