Cecilia Jane Reynolds

Images, Manuscripts, Artifacts

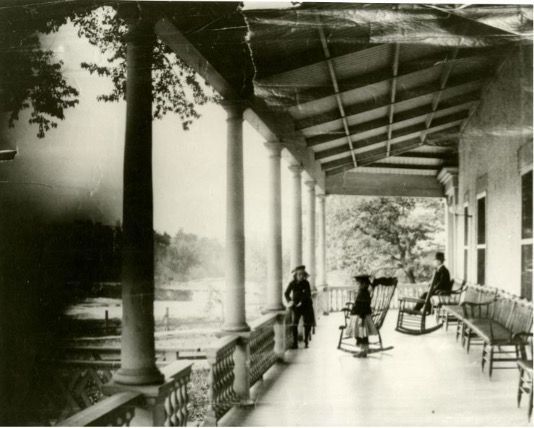

Porch of the Cataract House

Courtesy Niagara Falls (New York) Public Library

On May 14, 1846, Louisville lawyer Charles W. Thruston along with his son, Samuel and daughter Fanny signed the guest register at Niagara’s Cataract House. Fanny’s ladies’ maid, who took care of her clothing, did her hair, and kept her room tidy, was listed only as a “servant.”

Later that same day, the family went to visit Bath Island, a private resort that also had a guest book. There, Fanny signed both her name and that of her enslaved maid, Cecelia Jane Reynolds. Cecelia was only fifteen years old. Fanny’s wealthy parents had purchased her and her mother, Mamie, from a slave trader when Cecelia was a baby, and she and Fanny always traveled together.

Cecelia had terrible memories of seeing her father, Adam, sold away to the slave traders. She was only six when he was taken to a plantation in Alabama. She never forgot the sight of Adam Reynolds in chains, being led away from his family forever.

Bath Island Register, May 14, 1846, showing the signatures of Samuel Churchill Thruston, Charles W. Thruston and Fanny A. Thruston, plus the name of Cecelia Jane Reynolds, Fanny’s “servant,’ written in Fanny’s own handwriting.

Courtesy Niagara Falls (New York) Public Library

A few days after arriving at the Cataract House, Cecelia disappeared. The brave young woman had arranged her own escape before she left Louisville, Kentucky. Underground Railroad operators there sent word to Niagara Falls, New York, and Toronto, Canada. They informed antislavery activists in both places that the Thrustons were planning a trip to the famous Cataract House, and that Cecelia wanted to cross the Niagara River to find freedom in Canada.

Cecelia successfully reached what is now Ontario. She did so with the help of the Cataract House hotel waiters and a brave dining room steward employed aboard the City of Toronto steamer. His name was Benjamin Pollard Holmes. The vessel on which he worked traveled between Toronto and Queenston, near Niagara Falls on a daily basis. Benjamin was a freedom seeker from Virginia who sometimes helped other African Americans escape to Canada. He was a widower who had lost his wife a couple of years earlier, and Benjamin took Cecelia with him to his Toronto home. They were married that November, and she became stepmother to his two little boys.

While living in Toronto, Cecelia learned to write. She sent a letter to her former owners in the spring of 1852, seeking information about how to buy her mother from them. Fanny wrote back, beginning a remarkable correspondence that lasted many years.

Image:

Artist Raffi Anderian’s vision of Cecelia being rowed across the Niagara River in a small boat.

Used with permission of Raffi Anderian.

Manuscript

Fanny Thruston Ballard at Louisville, Kentucky, to Cecelia Jane (Reynolds) Holmes at Toronto, Canada, March 11, 1852. Courtesy Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Kentucky.

Louisville, March 11 th / 52

Pa received a letter from you, Celia, a few days ago, in which you make affectionate inquiries about all your family. He has received other letters from you at different times, all of which I read to your Mother and Brother . . .

I will first write of those in whom you are most interested and begin with your Mother. She was here yesterday; is beginning to show age a little, but is in most excellent health. She does not now belong to Pa. After my marriage she desired to be sold; but she frequently visits us and is exceedingly anxious that I should buy her, and bring her home to live again. She seems to be so much attached to us and always so good a servant that I wished to do so, but her present owner was unwilling to part with her. I told her however that I would always feel interested in her and would at any time be glad to have her live with me. She says she has a good home but would rather live with me than any one else. She frequently talks to me about you and always in tears expresses a hope to see you once more . . .

I hope Cecelia you are happy; much happier than when you were my property; and I trust you may always be surrounded by every comfort and blessing. If it should be never your lot to meet your parent on earth may God in his mercy and love gather you together in Heaven.

Yours &c

Fanny T. Ballard

In a later letter, Fanny told Cecelia that she could buy her mother’s freedom for $600, a huge amount of money in those days. Despite many efforts to raise the funds, Cecelia was not reunited with her beloved mother until after the Civil War.

Enslaved by Frances Thurston Ballard, Lexington, Kentucky, escaped from slavery at Niagara Falls and went to Toronto.

Artifacts:

Archaeologist and historian Karolyn Smardz Frost wrote a book detailing the life and experiences of Cecelia Jane Reynolds before and after she escaped via the Cataract House (Karolyn Smardz Frost, Steal Away Home (Toronto: HarperCollins Canada, 2017).

While she was completing the manuscript, she found out that archaeologists were digging the site of the home Cecelia had once shared with Benjamin in downtown Toronto. She couldn’t wait to visit the site and see the place where Cecelia and Benjamin had once lived!

In her book, Karolyn talks about her experience of standing where Cecelia had lived, worked, and written her letters to Fanny, who still resided in her old hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. The archaeologists even found a pottery inkwell in the backyard of Cecelia’s Toronto home. It might have been the one Cecelia used to write her letters to Fanny Thruston.

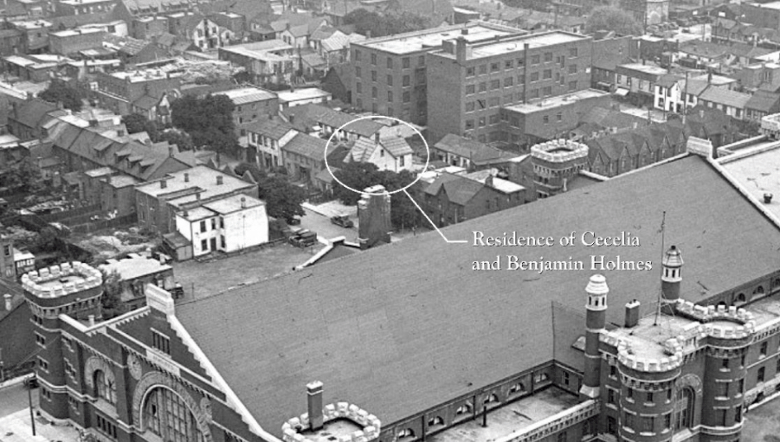

Home of Cecelia and Benjamin in downtown Toronto (the Armories are in the foreground)

Annotated image courtesy TIMHC Inc.

Photography origin: City of Toronto Archives.

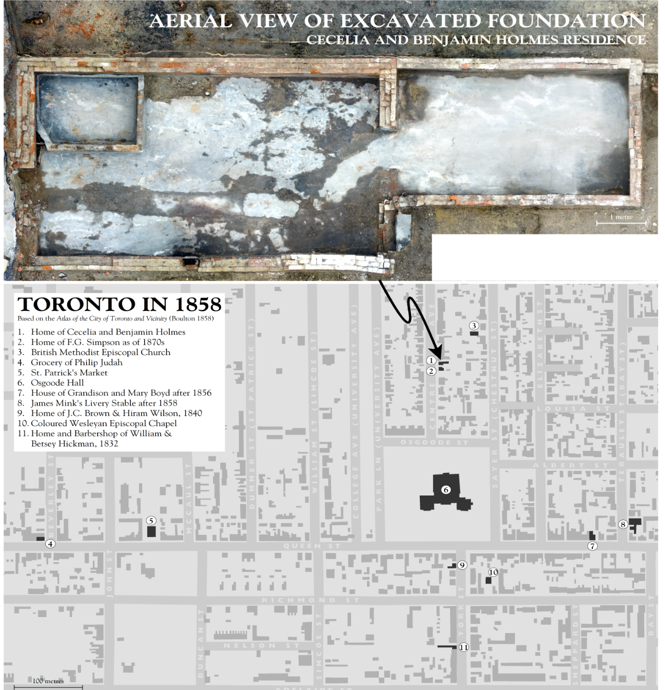

Aerial View of Cecelia and Benjamin’s Toronto Home, and

Historic Map of Toronto showing location of the Holmes’ family house

Images courtesy of TMHC Inc., London, Ontario.

Excerpt from Karolyn Smardz Frost, Steal Away Home (Toronto: HarperCollins Canada, 2017).

The very deepest layers of Lot 7 on the east side of Centre Street contained an intricately laid pattern of artifacts. These testify to the rather wonderful quality of life that Benjamin had provided for his little family. Their house itself may have been modest, but those sheltered by its walls lived well. There was a good deal of beautiful china and glassware found at the site, and one cannot help but envision Cecelia entertaining the church ladies in her small, tidy parlour. She poured tea from a majolica teapot into gilt-edged white porcelain cups, stirring in the milk she bought at Willis Addison’s grocery store with silver-plated spoons. Cakes she had made in the small kitchen addition at the rear of her home were set out on a lovely cobalt-blue glass plate, and the ladies ate them from pretty blue-sprigged plates that imitated Wedgwood’s best moulded jasperware.

Cecelia must have envied her neighbours their brown transfer-printed bowl bearing the scene from Uncle Tom’s Cabin of Eliza crossing the ice. The wealth of artifacts found on adjacent lots defies the modern view of St. John’s Ward as an irretrievably impoverished place to live. Although most of the residents worked with their hands, their household furnishings included porcelain tea sets, pressed glass tumblers, framed prints and fancy hardware for the doors and windows. Lace curtains hung from brass rods at their windows, and their children attended school in spotless pinafores and shiny black boots whose buttons were found scattered throughout the yards of these cottage homes.

While her mother served tea, Cecelia’s daughter Mamie played quietly with a china doll. Its cloth body has long since disappeared, but a diminutive china leg was found buried at the deepest levels of the backyard. The leg was white, but the little girl of African-Canadian barber Edward Jones, a few doors up the street, had one whose shiny black porcelain head reflected her own African heritage. . .

After the evening meal, Cecelia might sit down to write yet another letter to her old mistress in faraway Louisville. Quarters would surely be cramped if her mother Mary’s purchase could be arranged and the older woman came to live with them, as was Cecelia’s fondest dream. Sitting at the well-scrubbed kitchen table, she painstakingly formed her letters. Her steel-nibbed pen has long rusted away, but the bowl of the stoneware inkwell into which she dipped it survives, part of a rather elaborate writing set recovered from a refuse pit at the rear of her yard.

Sprigged china plate from Lot 7, Courthouse Site. Image courtesy Infrastructure Ontario.

Stoneware inkwell discovered in refuse (garbage) pit in the rear of Cecelia and Benjamin’s yard, Courthouse Site. Image courtesy Infrastructure Ontario.

Transfer ware soup plate with image of Eliza Crossing the Ice from Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)

Courthouse Site, Toronto. Image courtesy Infrastructure Ontario.

China doll’s head with black glazing, made for the African American market by a German manufacturer. Courthouse Site, Toronto. Image courtesy Infrastructure Ontario.