Niagara City or Suspension Bridge

T.D. Judah. Map of the Villages of Bellevue, Niagara Falls, and Elgin, 1854.

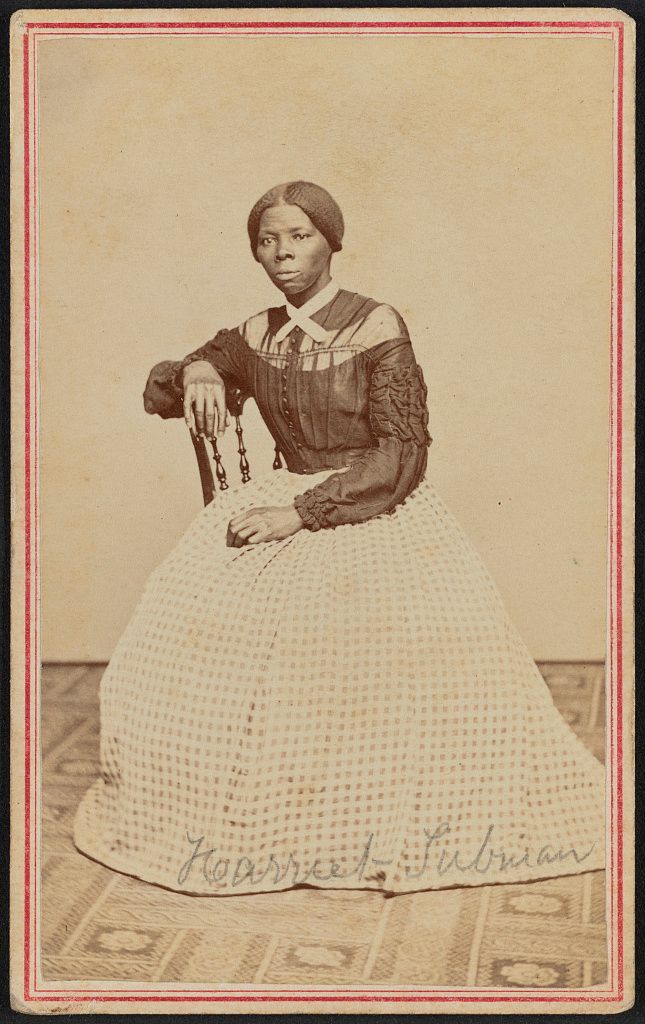

Harriet had been this way before. Like any tour guide anxious to show off the local sights, she called her companions to look at the Falls. Peter, Eliza, and William were impressed, but Joe still sat with his head in his hands. Harriet scolded him. "Joe, come look at de Falls! Joe, you fool you, come see the Falls! It’s your last chance." Joe still sat. When they reached the middle of the bridge, Harriet knew they were at last in Canada, and she raced to Joe’s seat, shook him as hard she could, and shouted, "Joe, you've shook de lion's paw!" [This is a reference to the British Lion, symbol of the Crown, that provided protection to freedom seekers on Canadian soil.] Bewildered, not knowing what they meant, Joe just looked at her.

"Joe, you're free!" shouted Harriet. Finally Joe responded. He raised his hands to heaven, and with tears streaming down his face, he started to sing in “loud and thrilling tones”:

Glory to God and Jesus too,

One more soul is safe!

Oh, go and carry de news,

One more soul got safe.

Joe leaped off the train. People gathered around him as he continued to sing “Glory to God and Jesus too, One more soul is safe!”

William and Peter, embarrassed, grabbed his arm and shouted, “Joe, stop your noise! You act like a fool!” and “Joe, stop your hollering! Folks’ll think you’re crazy!” But Joe kept singing.

"Oh! if I'd felt like this down South, it would have taken nine men to take me,” he shouted. “Only one more journey for me now, and that is to Heaven!"

Harriet’s response? "Well, you old fool you." "You might have looked at the Falls first, and then gone to Heaven afterwards."

Instead of heaven, the whole group went to St. Catharines, where American missionary Rev. Hiram Wilson operated a fugitive aid society. Wilson reported that Tubman was “a remarkable colored heroine,” “unusually intelligent and fine appearing,” and the men she brought were “of fine appearance and noble bearing.”[1]

This story illustrates the remarkable importance of Niagara Falls as a major Underground Railroad crossing point from the United States to Canada. For white tourists and traders, crossing the river on the ferry and Suspension Bridge meant entertainment or financial gain. For African Americans escaping from slavery, however, this journey was, literally, a life-changing experience, a trip from slavery to freedom. Crossing the river—enveloped by mist from the Falls or viewing the cataract from afar on the bridge—must have seemed to many like a rebirth, a chance to start life anew, free from the violence and threat of sale that had driven them to escape from slavery in the first place.

Document 1:

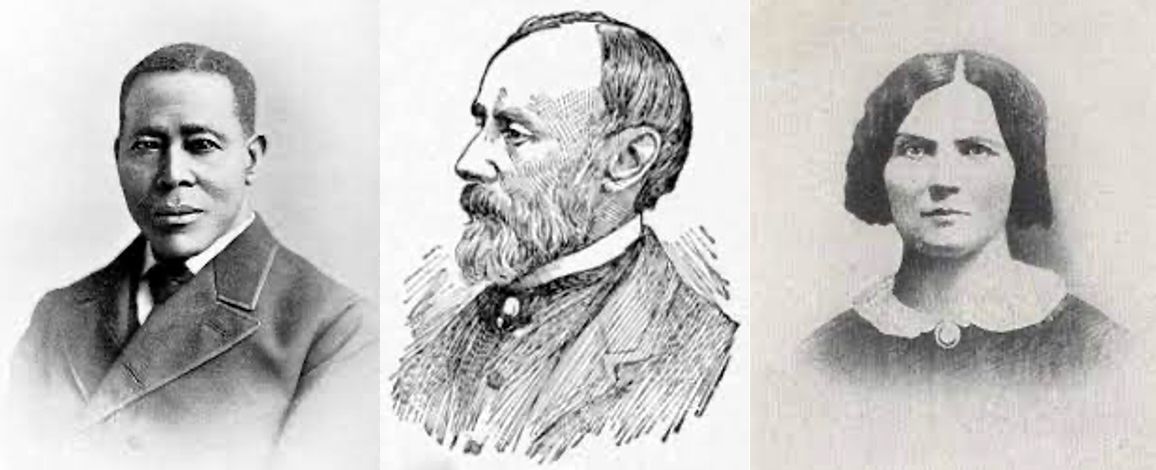

William Still kept the most important Underground Railroad station in Philadelphia in the 1850s. Still kept a journal, recording details of each African American freedom seeker who came through his office. He wrote this detailed description of Joseph Bailey and William Bailey, noting also that Peter Pennington and Eliza Manokey (Nokey) had been assisted by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.

HEAVY REWARD.

TWO THOUSAND SIX HUNDRED DOLLARS REWARD.-Ran away from the subscriber, on Saturday night, November 15th, 1856, Josiah and William Bailey, and Peter Pennington. Joe is about 5 feet 10 inches in height, of a chestnut color, bald head, with a remarkable scar on one of his cheeks, not positive on which it is, but think it is on the left, under the eye, has intelligent countenance, active, and well-made. He is about 28 years old. Bill is of a darker color, about 5 feet 8 inches in height, stammers a little when con-fused, well-made, and older than Joe, well dressed, but may have pulled kearsey on over their other clothes. Peter is smaller than either the others, about 25 years of age, dark chestnut color, 5 feet 7 or 8 inches high.

A reward of fifteen hundred dollars will be given to any person who will apprehend the said Joe Bailey, and lodge him safely in the jail at Easton, Talbot Co., Md., and $300 for Bill and $800 for Peter, W. R. HUGHLETT, JOHN C, HENRY, T. WRIGHT.

When this arrival made its appearance, it was at first sight quite evident that one of the company was a man of more than ordinary parts, both physically and mentally. Likewise, taking them individually, their appearance and bearing tended largely to strengthen the idea that the spirit of freedom was rapidly gaining ground in the minds of the slaves, despite the/efforts of the slaveholders to keep them in darkness. In company with the three men, for whom the above large reward was offered, came a woman by the name of Eliza Nokey. As soon as the opportunity presented itself, the Active Committee feeling an unusual desire to hear their story, began the investigation by inquiring as to the cause of their escape, etc., which brought simple and homely but earnest answers from each. These answers afforded the best possible means of seeing Slavery in its natural, practical workings-of obtaining such testimony and representations of the vile system, as the most eloquent orator or able pen might labor in vain to make clear and convincing, although this arrival had obviously been owned by men of high standing. The fugitives themselves innocently stated that one of the masters, who was in the habit of flogging adult females, was a "moderate man." Josiah Bailey was the leader of this party, and he appeared well-qualified for this position. He was about twenty-nine years of age, and in no particular physically, did he seem to be deficient. He was likewise civil and polite in his manners, and a man of good common sense. He was held and oppressed by William H. Hughlett, a farmer and dealer in ship timber, who had besides invested in slaves to the number of forty head. In his habits he was generally taken for a "moderate" and "fair" man, "though he was in the habit of flogging the slaves-females as well as males," after they had arrived at the age of maturity. This was not considered strange or cruel in Maryland. Josiah was the "foreman" on the place, and was entrusted with the management of hauling the ship-timber, and through harvesting and busy seasons was required to lead in the fields. He was regarded as one of the most valuable hands in that part of the country, being valued at $2,000. Three weeks before he escaped, Joe was "stripped naked," and "flogged" very cruelly by his master, simply because he had a dispute with one of the fellow-servants, who had stolen, as Joe alleged, seven dollars of his hard earnings. This flogging, produced in Joe's mind, an unswerving determination to leave Slavery or die: to try his luck on the Underground Rail Road at all hazards. The very name of Slavery, made the fire fairly barn in his bones. Although a married man, having a wife and three children (owned by Hughlett), he was not prepared to let his affection for them keep him in chains-so Anna Maria, his wife, and his children Ellen, Anna Maria, and Isabella, were shortly widowed and orphaned by the slave lash.

WILLIAM BAILEY was owned by John C. Henry, a large slave-holder, and a very "hard" one, if what William alleged of him was true. His story certainly had every appearance of truthfulness. A recent brutal flogging had "stiffened his back-bone," and furnished him with his excuse for not being willing to continue in Maryland, working his strength away to enrich his master, or the man who claimed to be such. The memorable flogging, however, which caused him to seek flight on the Underground Rail Road was not administered by his master or on his master's plantation. He was hired out, and it was in this situation that he was so barbarously treated. Yet he considered his master more in fault than the man to whom he was hired, but redress there was none, save to escape. The hour for forwarding the party by the Committee, came too soon to allow time for the writing of any account of Peter Pennington and Eliza Nokey. Suffice it to say, that in struggling through their journey, their spirits never flagged; they had determined not to stop short of Canada. They truly had a very high appreciation of freedom, but a very poor opinion of Maryland.

William Still, The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia, 1872), 272-74,

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15263/15263-h/15263-h.htm.

Document 2:

William Still sent this group to the office of the National Anti-slavery Standard in New York City, where editor Sydney Howard Gay kept an Underground Railroad station, with the help of African American activist Louis Napoleon and others. Gay also kept a journal. In this selection, he quotes William Bailey (alias William Smith) as Bailey describes both his own experience and that of Eliza Manokey.

P. 5 Antislavery Office Nov 26/56

William Bailey (alias Wm. Smith) says he left Jamaica Point, Talbot County, Maryland, on the night of 15th inst, in company with two other men bound on the same errand, a journey to the north, and travelled 25 miles before 12 o’clock when he fell in with a woman staying at the house of a friend where she had been since January last when she attempted to take herself away. We arrived safe in Philadelphia on Monday night last, and there being a large reward offered for our recovery – $2600 – we were, there were four of us, divided. I being sent alone, the others are expected tomorrow. Smith says he left a wife and four children respectively aged 7 years, 4 years, 2 years, and 10 mos. His wife is aged 25, he is 32. Smith says he left his master on account of ill-treatment, of which lately he has received more than he could or would bear. Smith says he has worked a steam engine for the last 30 months. And further saith not. [Woman presumably Eliza Manoga [Manokey]]

P. 6

[On reverse]

Statement from William Bailey alias William Smith Nov 26/56 P. 7. Nov. 27. Eliza Manoga [Manokey], from Dorchester Co., Md. About 42 yrs. old. Ann Greaves, her owner, had hired her away so far from her husband (who is free) that she ran away rather than go. Has two children, son and daughter. Mistress gave the son to her newphew [sic], who took him to Missouri when he was 4 yrs. old. The boy clung frantically to his mother, begging her to save him, but in vain. Never heard from him since. The daughter is now 16 or 17, belongs to the mother’s mistress, has four children. First ran away in January last, took refuge in the woods, alone.

P. 8 Free colored families aided her. Laid out in the woods till wheat harvest. Then came to Del[aware]. and staid [sic] till first Nov. “My Savior protected me and I trusted in him. I did not even get frosted [frostbitten].” Often suffered for want of food and clothing, and often flogged. A brave earnest woman. (Came with Harriet Tubman.) Went to Canada. Sent her to Troy, needed no money.

Sydney Howard Gay “Record of Fugitives,” Book 2, 5-8, Columbia University,

https://exhibitions.library.columbia.edu/exhibits/show/fugitives/record_fugitives/transcription).

For more information and background, see Kate Clifford Larson, Harriet Tubman: American Hero, 133-36; Don Papson and Tom Calarco, Secret Lives of the Underground Railroad in New York City: Sydney Howard Gay, Louis Napoleon, and the Record of Fugitives (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2015); and Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York: Norton, 2015).