The Evans Girl

1841: Newspaper Articles, Map, Image

Overview

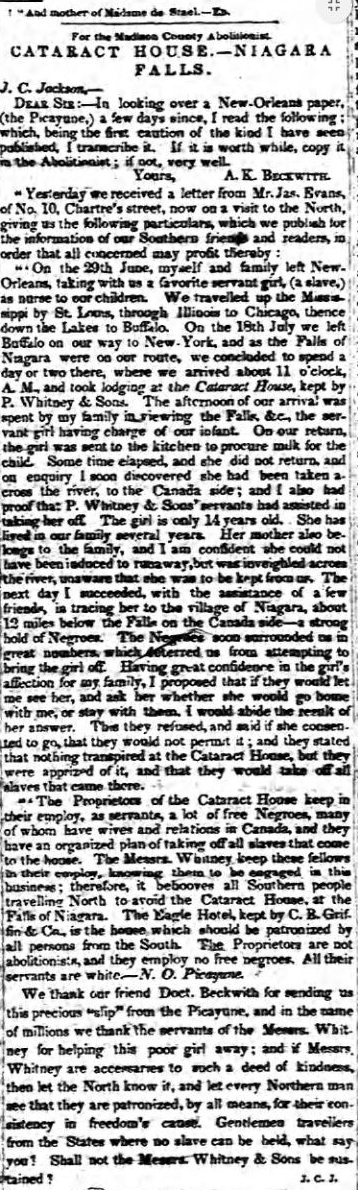

The August 4, 1841, issue of the New Orleans Daily Picayune included a letter to the editor describing the flight of a fourteen-year-old maidservant from the famed Cataract House hotel at Niagara Falls, New York. The author was James S. Evans, a prosperous hat merchant with a shop at 10 Rue Chartres. He and his wife had taken their enslaved nursemaid along on vacation with them to care for their young family. Sent to the hotel kitchens to acquire milk for the Evans baby, the young woman never returned.

Evans and some of his fellow hotel guests eventually located her, hidden in a private home at the Canadian village of “Niagara” (Niagara-on-the-Lake), where the Niagara River met Lake Ontario, about twelve miles north of the falls. Arriving at this “stronghold of Negroes,” he and his supporters were confronted by an angry crowd that refused to let Evans communicate with his former “servant.” Eventually the furious slaveholder and his friends crossed back to the American side of the river. The Evans family returned to New Orleans, but they did so without their maid.

In his letter, James S. Evans accused the Cataract House staff of “enticing” the woman to run away and warned fellow slave owners that the hotel’s owners had been complicit in her escape:

The proprietors of the Cataract House keep in their employ, as servants, a set of free negroes, many of whom have wives and relatives in Canada, and they have an organized plan of taking off all slaves that come to the house. The Mesers. Whitney [sic] keep these fellows in their employ, knowing them to be engaged in this business; therefore it behooves all Southern people traveling North to avoid the Cataract House at the Falls of Niagara.

Evans’s story was corroborated by a reporter for the New York Herald, who added, “Southern gentlemen who take their servants with them, should be careful where they lodge – and hotel keepers, who have colored persons for servants, should be careful of their inmates.”

The Madison County Abolitionist took a different view. The editor assumed that the owners of

the Cataract House had indeed been involved in “the poor girl’s escape” and suggested that “every Northern man [should] see that they are patronized, by all means, for their consistency in freedom’s cause.”

The details of this unnamed woman’s flight to freedom offer fascinating insight into the mechanisms that facilitated antebellum Black transnationalism along the Niagara frontier. While such cross-border transfers were both illegal and dangerous, and became more so in the years leading up to the Civil War, the significance of the Cataract House as a nexus of Underground Railroad-era activism is well documented.

However, it was not the Whitneys but rather the African American staff of their popular hotel who ran the highly efficient Underground Railroad station there. Furthermore, James Evans was quite right in suggesting that these anti-slavery-minded workers at that Cataract House depended on the support of African Canadian friends and relatives across the Niagara River for ensuring the successful escape of uncounted numbers of freedom seekers.

Adapted from Karolyn Smardz Frost, “The Cataract Hotel: Underground to Canada through the Niagara River Borderlands,” in Natalee Caple and Ronald Cummngs, eds, Harriet's Legacies : Race, Historical Memory, and Futures in Canada (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2022). ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/dal/detail.action?docID=29289876.

Newspaper Articles. Several newspapers across the country published accounts of this story.

1. New Orleans Daily Picayune, August 4, 1841.

“The proprietors of the Cataract House keep in their employ, as servants, a set of free negroes, many of whom have wives and relatives in Canada, and they have an organized plan of taking off all slaves that come to the house. The Messrs. Whitney keep these fellows in their employ, knowing them to be engaged in this business; therefore it behooves all Southern people traveling North to avoid the Cataract House at the Falls of Niagara.”

2. "Abduction" of female slave from owner from New Orleans at the Cataract House at Niagara Falls. National Anti-Slavery Standard, August 28, 1841.

“An Abduction at Niagara Falls.—Our Buffalo correspondent, to-day, relates a story of the abduction of a female servant from a southern gentleman, who visited Niagara Falls, and stopped at the Cataract House. His statement we know to be a fact. We have seen the gentleman to whom the girl belonged, and he has confirmed every particular. He is from New Orleans.

Southern gentlemen who take their servants with them, should be careful where they lodge—and hotel keepers, who have colored person for servants, should be careful of their inmates.”

3. Madison County Abolitionist, November 2, 1841

Madison County Abolitionist, November 2, 1841

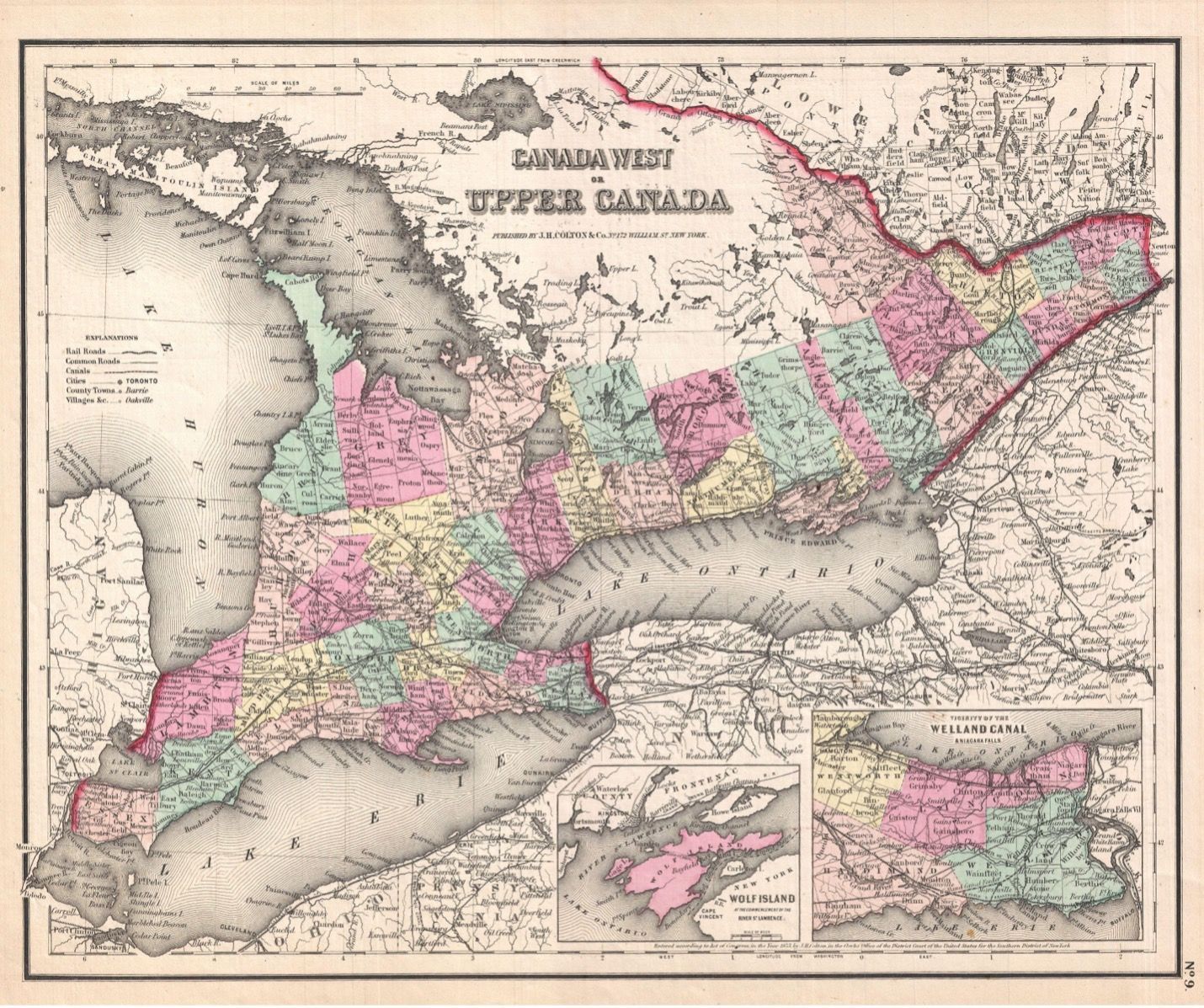

Map

Beginning in 1833, Joseph Hutchings Colton (joined later be his sons G.W. and C.B. Colton), published detailed maps from their offices in New York City. This beautifully illustrated map of Upper Canada (now Ontario) first appeared in Colton’s Atlas of the World (1855).

1855: J.H. Colton, Canada West or Upper Canada from G. W. Colton, Colton's Atlas of the World

Illustrating Physical and Political Geography, Volume 1, (New York, 1855)

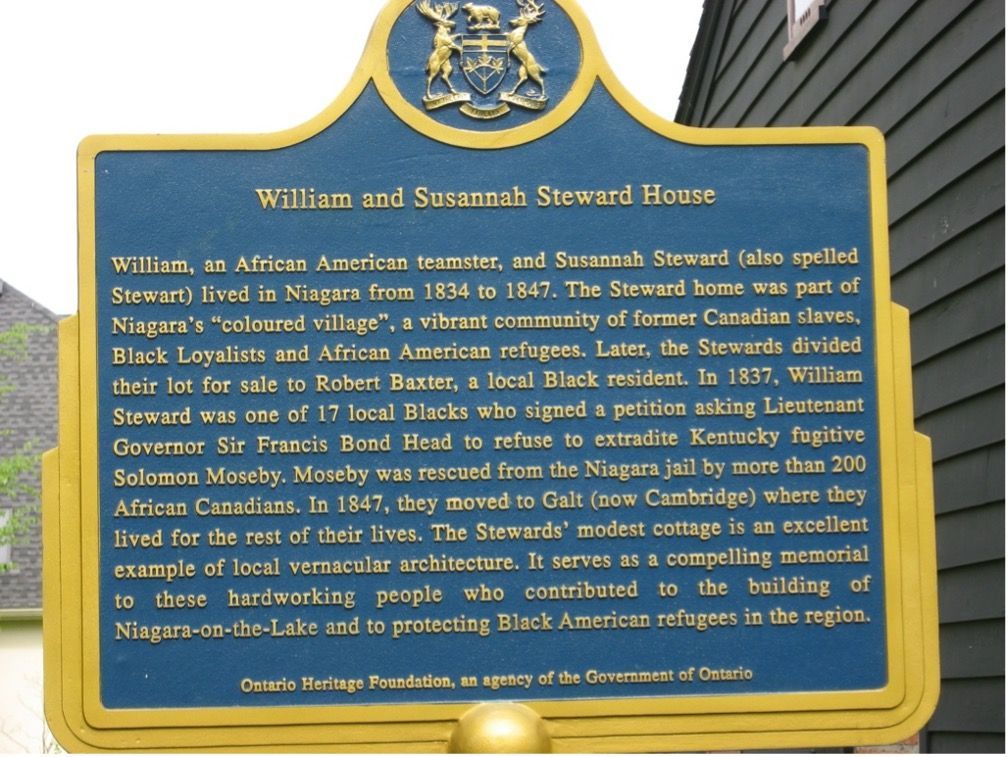

Image

By the 1850s, the “Colored Village” of Niagara-on-the-Lake numbered about 400 people. This is the William and Susannah Steward House, built ca. 1837. It is the last standing home in what had been the Colored Village. The Stewards were politically aware and active. It is entirely possible that it was in this home that the Evans girl who fled via the Cataract House in 1841 was concealed, when she first came across the river from Niagara Falls, New York.

William and Susannah Steward House

Photo by Karolyn Smardz Frost, 2023

Plaque

William and Susannah Steward lived in the “coloured village” of Niagara-on-the-Lake from 1834 to 1847. When the Evans girl escaped from slavery, she may have stayed in this house or one very much like it. Karolyn Smardz Frost wrote the text for this plaque erected by the Ontario Heritage Foundation.

Plaque: William and Susannah Steward House

Photo by Karolyn Smardz Frost, 2023