Niagara Falls Underground Railroad

Overview

Project: From the Cataract House to Canada on the Underground Railroad

From the very beginning of post-Seneca settlement, people of African descent joined people of Native and European descent in creating a vibrant tourist economy in Niagara Falls. They also developed a major Underground Railroad crossing from slavery in the U.S. to freedom in Canada.

Escape to what is now Ontario through Niagara County began as early as 1802, when William Riley drove his enslaver from Fredericksburg, Virginia, to visit the Falls. Instead of returning South, Riley made his way across the river, where he settled in Niagara-on-the-Lake and became a respected farmer.

Other scattered flights to freedom occurred in the 1820s. A trickle of escapes occurred in the 1830s, escalating in the 1850s to a flood.

Of the sixty-seven documented stories of escape from slavery by way of Niagara County between 1802 and 1860, twenty-one related directly to the Cataract House hotel. (A cataract is a huge waterfall, such as the one at Niagara Falls). Waiters at the Cataract House, including head waiter John Morrison, regularly rowed “star-led fugitives” across the river to freedom.[1]

Ferry Boats crossing Niagara River

Stereopticon View, c. 1865, Niagara Falls (NY) Public Library

Fifteen known escapes were made across the new Suspension Bridge, built two miles north of the Cataract House. People crossed on foot or by wagon after 1848 and then on the railroad after the bridge opened to rail traffic in March 1856.

Another fourteen incidents related to Lewiston or Youngstown, the other two main river crossings in Niagara County. We cannot identify specific crossing points for the remaining seventeen refugee tales. We can be sure, however, that these written documents record only a small portion of the total number of people who escaped along the Niagara Fronter. By 1860, 30,000-40,000 people of color lived in what is now Canada. Many of these certainly crossed into freedom through Niagara Falls.

Charles Parsons, "The Rail Road Suspension Bridge: Near Niagara Falls”

(New York: Currier & Ives, 1857).

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, I.D. cph.3b51175.

Waiters at the Cataract House played a key role. They would help freedom seekers steal away under cover of darkness to Prospect Point, right at the edge of the Falls. From there, they would descend a steep staircase to the rocks at the edge of the river, stepping into rowboats tethered there. These small craft served during the day as ferries for tourists. Head waiter John Morrison and others would row their precious cargo across the roiling water. In eight to fifteen minutes, they would be at the dock in Canada. There, they would be welcomed by African Canadian families and sent on to places such as Niagara-on-the-Lake, St. Catharines, Hamilton, Buxton, or Toronto.

Some freedom seekers came to the Cataract House in slavery. About twenty percent of guests listed in Cataract House registers gave their place of residence as a southern state. Often, Southern white families would bring their enslaved servants with them as maids, valets, or nannies. Waiters would approach visitors of color and ask if they would like to go to freedom across the river. Many responded with an enthusiastic “yes!”

By the 1850s, many people who escaped from slavery had learned about the help they could receive at the Cataract House. Particularly after passage of the incredibly harsh new federal Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, people began to arrive regularly in Niagara Falls from Maryland, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere sent by way of a Quaker-dominated network in southeastern Pennsylvania via road, river, or railroad. Others came from states farther west or south, including Kentucky and South Carolina. Some may have been assisted by a network of Indigenous people, headed for Tuscarora homelands north of Niagara Falls and or the Mohawk Reserve along the Grand River in what is now Ontario.

Waiters at the Cataract House were very effective and increasingly well-known as agents of the Underground Railroad. In 1854, the Onondaga Gazette noted: THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD. -The splendid Double Track Broad Gauge [sic] Underground Railroad, from the mouth of the Niagara river to the sunny South, is now open for the transit of passengers.” In 1859, the Niagara Falls Gazette reprinted an article from the Troy Arena, noting that the Underground Railroad “has been doing an unusually large business this year. Some days the ‘train’ takes a dozen at a time, and the aggregate business of the year is counted by the hundreds.” As one observer noted, “They call it the Underground Railroad. They must go under ground or by balloon, for once in his hands they are never seen again this side of the river."[1]

For people seeking freedom, this journey was, literally, a life-changing experience, a trip from a lifetime in slavery to a future in freedom. Crossing the river—enveloped by mist from the Falls or viewing the great waterfall from afar on the bridge—must have seemed like a rebirth, a chance to start life anew, free from the violence and threat of sale they had endured for so long.

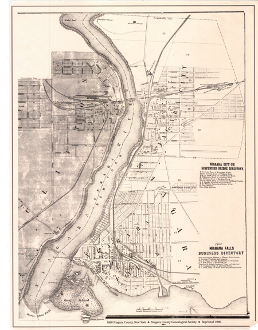

Map. This map of Niagara Falls in 1860 shows the Cataract House, the ferry landing, the route of the ferry from Prospect Point to Niagara Falls, Ontario, and the Suspension Bridge. All of these sites played key roles in the escape of people from slavery to freedom through Niagara Falls.

Niagara Falls, New York, 1860, from O.W. Gray, Map of Niagara and Orleans Counties, New York

(Philadelphia: Published by A.R.Z. Dawson, 1860).

Courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Maps Division, 2013593264,

http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3803n.la000523

Image: Augustus Kollner painted this view of the ferry landing on the Canadian side of the river in about 1850.

Augustus Kollner, “General View,” Views of American Cities

(New York and Paris:Goupil, Vibert, and Company, 1849-51).

http://www.castellaniartmuseum.org/assets/Art/Items/3-v2__ScaleMaxWidthWzEyMDBd.jpg

Underground Railroad stories in this section focus on five documented Underground Railroad tales related to the Cataract House. They are listed here by time period. For a good introduction to the Underground Railroad and the Cataract House, read the story of John Morrison and Rachel Smith first, and then the Escape Routes: Ferry Landing, in section VI.