Patrick Sneed

1853: Creative Storytelling, Memoir, Newspaper Articles, Census Record

Context

Red-haired and freckled, Sneed was raised in Savannah, Georgia. He was descended from Jewish, African American, and Native American ancestors. Sneed escaped from slavery in 1849 and lived first in Brantford, Canada West, and then in Toronto. By August 1853 he was working as a waiter at the Cataract House in Niagara Falls, New York, under the assumed named of Joseph Watson. [1] He used the name of a local man whom he had encountered in Brantford, in order to conceal his identity as a refugee from slavery.

But someone, perhaps one of the Cataract House’s many Southern visitors, recognized Patrick Sneed. On Sunday afternoon, August 27, 1853, about 4:00 p.m., two police officers—J.K. Tyler and Eli Boyington—arrived at the Cataract House with a warrant for Sneed’s arrest. What happened next is best told through Patrick Sneed’s own recollections and by several newspaper articles.

Tyler, Boyington and a deputy named John Pierce appeared at the Cataract House, its proprietors hotel was now in the hands of Parkhurst and Celinda Whitney’s son, Solon Whitney, two sons-in-law, Dexter Jerauld, and James F. Trott. They asserted that they had no wish to obstruct justice, but they declined to help the marshals arrest Watson/Sneed. The officers then resorted to a ruse: they called Sneed out of the dining room, pretending that they wished to tip him for service at dinner. Immediately, Boyington clapped handcuffs on one of Sneed’s wrists, but Sneed “shouted lustily for assistance.” Between sixty and one hundred waiters poured out of the dining room to help him. They dragged Sneed back into the dining hall, tore him from the hands of the officers (in the process ripping “nearly every vestige of his clothing” from him), and then shut and barred the doors at the end of the hall. There they stood guard, preventing the officers from following.[2]

In his own words, Patrick Sneed recounted what happened next:

Then a constable of Buffalo came in, on Sunday after dinner, and sent the barkeeper into the dining-room for me. I went into the hall, and met the constable--I had my jacket in my hand, and was going to put it up. He stepped up to me. "Here, Watson," (this was the name I assumed on escaping,) "you waited on me, and I'll give you some change." His fingers were then in his pocket, and he dropped a quarter dollar on the floor. I told him, "I have not waited on you--you must be mistaken in the man, and I don't want another waiter's money." He approached,--I suspected, and stepped back toward the dining-room door. By that time he made a grab at me, caught me by the collar of my shirt and vest,--then four more constables, he had brought with him, sprung on me,--they dragged me to the street door-- there was a jam--I hung on by the doorway. The head constable shackled my left hand. I had on a new silk cravat twice round my neck; he hung on to this, twisting it till my tongue lolled out of my mouth, but he could not start me through the door. By this time the waiters pushed through the crowd,--there were three hundred visitors there at the time,--and Smith and Grave, colored waiters, caught me by the hands,--then the others came on, and dragged me from the officers by main force. [3]

Few people in the hotel seemed to want to help the marshals capture Sneed, but several defended him. When one hotel guest shouted for help for the officers, “none appeared anxious to interfere.”[4] . . .

Too late. As Sneed described the chase that followed, waiters “dragged me over chairs and every thing, down to the ferry way. I got into the cars [the inclined railway had been built in 1845], and the waiters were lowering me down, when the constables came and stopped them, saying, "Stop that murderer!"--they called me a murderer! Then I was dragged down the steps by the waiters, and flung into the ferry boat.” He made it within fifty feet of the Canadian shore before the ferryman discovered that he was carrying an accused murderer. Instead of taking Sneed to Canada, he brought Sneed back to the American shore. “They could not land me at the usual place because of the waiters,” Sneed recounted, so they took him to the Maid of the Mist landing, just south of the Suspension Bridge.

The chase was not yet over. As Tyler and Boyington ran to the dock, they were followed by “troops of negroes,” about 250 to three hundred of them, with waiters from the Cataract joined by waiters from other hotels and throughout the village, “all the black population of the place,” “armed.” They met the ferryboat at the Maid of the Mist landing. However, the two officers recruited “a band of Irish laborers,” about two to three hundred in number, living in the village. In the resulting fracas, “long and severe,” Blacks yielded to Irish assailants. Officers Tyler and Boyington shackled Sneed, bundled him into a carriage and boarded the train to Buffalo.

Even at the time of Sneed’s arrest, many people considered the charges to be false, and thought such accusations were simply an attempt to get to re-enslave Patrick Sneed. Nevertheless, Sneed was jailed by police justice Isaac P. Vanderpoel at 10:00 p.m. that evening. Sneed immediately asked to see a lawyer. Sneed did not name this man in his 1856 account, but he engaged a local attorney named Eli Cook, who hated slavery and defended Sneed throughout his ordeal. The constables were “astonished” to see that Sneed had hired “one of the best lawyers in the place.” Sneed told them that "as scared as they thought I was, I wanted them to know that I had my senses about me." [5]

The trial began ten days later, and it was over on day eleven. New information came to light, including a letter from Alfred E. Jones (supposedly the brother of the murdered man) to Joseph K. Tyler. Jones offered Tyler $300 in cash for the delivery of Sneed. The court required a proper affidavit, and Jones assured Marshal Tyler that he would have it within two weeks. “You have the right man,” he wrote on August 31, “and you can swear to the fact, as I had him spotted there, and the person that saw him the day before you arrested him, knew him well, and recognized him as the man. . . . Do not let him escape, as I shall not fail to put you in possession of the right paper.” Tyler heard nothing more from Jones.

Savannah witnesses wrote, declaring both Patrick Sneed and his half-brother Adam Mendenhall to be innocent of murder. Judge Mordecai Sheftall wrote from Savannah,

Such a rumor, that either Adam Mendenhall, or his brother Patrick, knew anything or was in any way concerned in the perpetration of the act, never prevailed in Savannah, and does not now prevail. I state to you sir, positively, that no affidavit was ever made by any person or persons against Adam or his brother Patrick, charging them with the murder of Jones, nor have any warrants founded on affidavits been issued against them. The design of Mr. David R. Dillon in moving in this business, is to obtain the possession of his slave Patrick. . . . He well knows they are not guilty of Jones’ murder, but it is the only plan he could devise, they being in a free State, to obtain the possession of his slave. [6]

Toward the end of the hearing, Charles Follett, District Attorney of Licking County, Ohio, doubtless must have made the audience gasp when he testified that he thought letters written by Alfred E. Jones were in the same hand as those written by David R. Dillon. Sneed’s counsel, Eli Cook, took two hours to sum up his argument, in a “most thorough, fair, and beautiful manner,” reported the Albany Evening Journal, and “the intentions in regard to Sneed are as clear as the dawn.” Judge Sheldon thought so, too. On day eleven, court opened at 9:00 a.m. and the judge released Sneed by 10:00 a.m. Sneed immediately left for Canad. Most likely, he crossed the river at Black Rock. [7]

The verdict of innocence received confirmation when Judge Sheldon received a letter from a slaveholder in Savannah:

There is but one opinion about the matter, and that is, that you acted perfectly right in discharging the man. The whole matter was fraud from beginning to end... and everyone here was very indignant that Dillon should try to impose upon the officers and Court at Buffalo in such a manner. Mr. Alfred E. Jones and David R. Dillon are one and the same man, as you suspected, and no one here believes that Patrick is the murderer of James W. Jones, and Dillon does not believe it. It was by fraud that he got him arrested, and it was by fraud that he obtained the requisition from Gov. Cobb. The persons I have these facts from are all slaveholders, and some of them lawyers, and all are respectable, and I assure you that the people of Savannah justify you in the course you pursued.[8]

In a story that received international attention, Patrick Sneed was captured, not as a fugitive from slavery, but as an accused murderer. He was brought before a federal marshal in Buffalo. Recognizing that the murder charge was false (invented by his enslaver, who realized that public opinion would not allow him to recapture Sneed as a freedom seeker), the judge freed Patrick Sneed. Sneed went immediately to Canada West (Ontario). He walked to the Clifton House in Niagara Falls, directly across the river from the Cataract House, and from there home to Toronto. Three years later, Sneed was still living in the city, still missing his lucrative job as a waiter at the Cataract House and having “hardly got over” the cost of paying his lawyer.[9]

Although more dramatic than most, Sneed’s story echoes the experience of thousands who left slavery for freedom through Niagara Falls. Beyond secret missions at night, waiters and their allies took to the streets to protect those in danger. Sneed’s escape represents the extent to which waiters and their allies in Niagara Falls would go to help people on their way from slavery to freedom.

[1] This account is an adaptation from that in Judith Wellman, “Historic Sites Relating to the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism, and African American Life in Niagara Falls, New York,” Appendix C, Heritage Area Management Plan (2012), 73-77

[2] Buffalo Daily Courier, August 30, 1853; Niagara Courier, August 31, 1853; Utica Daily Gazette, August 31, 1853; Syracuse Daily Standard, August 31, 1853, copied from the Buffalo Republic.

[3] Benjamin Drew, A North-Side View of Slavery. The Refugee: or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in

Canada. Related by Themselves (Boston: J.P. Jewett, 1856), 102-03.

[4] Buffalo Daily Courier, August 30, 1853; Niagara Courier, August 31, 1853; Utica Daily Gazette, August 31, 1853.

[5] Benjamin Drew, A North-Side View of Slavery. The Refugee: or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada. Related by Themselves (Boston: J.P. Jewett, 1856), 103.

[6] Mordecai Sweetall [Sheftall] to O.A. Blair, February 12, 1854, reported in Albany Evening Journal, September 9,

1853.

[7] Albany Evening Journal, September 9, 1853; Benjamin Drew, North-Side View of Slavery (1856), 104.

[8] Schenectady Cabinet, November 22, 1853, copied from the Buffalo Express; Northern Christian Advocate,

November 23, 1853, copied from the Buffalo Republic.

A waiter who is believed to have served at the Cataract House

Image discovered by Ally Spongr DeGon

Newspaper articles:

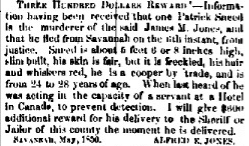

Three substantial rewards awaited the person who captured the murderer of James W. Jones, one for $1500, another for $1000, and a third for $300. One of them described Patrick Sneed’s appearance in detail.

Albany Evening Journal, September 9, 1853

Image

Here is a drawing of a man named Joshua Glover, who was captured in St. Louis, Missouri in 1852. With his vest, shirt with collar, and a new silk cravat, he may have looked very much like Patrick Sneed.

American Anti-Slavery Society, The Fugitive Slave Law and Its Victims, 1856.

Census Record

Two marshals captured Patrick Sneed in 1853, Joseph K. Tyler and someone listed only as as Mr. Boyington. Tyler is listed in the 1855 NYS census as a “Dep. Marshal,” age 41, born in Connecticut, living in Buffalo for 19 years, married to 36-year-old Susan A. Tyler, born in Chenango County, NY, living in Buffalo for 13 years, and their 13-year-old son, Joseph, and Ann Flanery, Irish-born servant (can’t read her age), living in Buffalo for four years. He is probably the “constable from Buffalo” mentioned in Sneed’s own detailed account.

Sources for the story of Patrick Sneed include: “The People vs Patrick Sneed: Opinion on Habeas Corpus, Sept. 8, 1853, in William Hodge Papers, Buffalo History Center, found by Cynthia Van Ness; Judith Wellman, “Cataract House,” Appendix C, Heritage Area Management Plan, 73-77, based on Sneed’s own account in Benjamin Drew, A North-Side View of Slavery. The Refugee: or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada. Related by Themselves (Boston: J.P. Jewett, 1856), 102-03; newspaper articles in the Buffalo Daily Courier, August 30, 1853; Niagara Courier, August 31, 1853; Utica Daily Gazette, August 31, 1853; Syracuse Daily Standard, August 31, 1853, copied from the Buffalo Republic; Albany Evening Journal, September 9, 1853; Schenectady Cabinet, November 22, 1853, copied from the Buffalo Express; Northern Christian Advocate, November 23, 1853, copied from the Buffalo Republic. The Buffalo Commercial Advertiser and the Buffalo Republic cited Officer Tyler as their direct source. For details, see Judith Wellman, Sites Relating to the Underground Railroad, Abolitionism, and African American Life in Niagara Falls (Appendix C, Heritage Area Management Plan, 2012, wwwniagarafallsundergroundrailroad.org), 73-77.