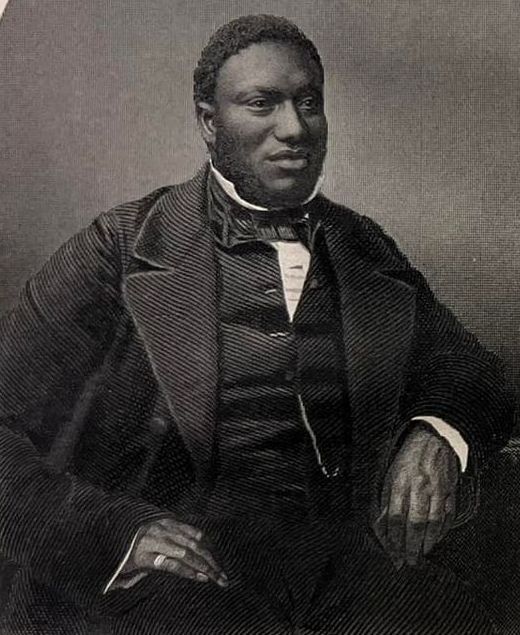

Overview

Samuel Ringgold Ward (1817-1866), born enslaved in Maryland. He and his family escaped when he was only three years old, and moved to the Northern US. The Wards went first to New Jersey and then to New York City, where Samuel attended the African Free School. As an adult, he became a minister, newspaper editor, author, and an internationally known abolitionist orator.

On January 11, 1853, Ward had just returned from a speaking tour in Great Britain, where he raised money for the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada. On the bitterly cold day of January 11, 1853, he was traveling from Canada to New York State with Reverend Hiram Wilson, an American missionary of European descent who worked with freedom seekers in Canada. In the ferry office of what is now Niagara-on-the-Lake in Ontario, Canada, they met a man dressed only in cotton clothing and an oil cloth coat. He was obviously a refugee, and he sat hunched around the stove, shivering.

Here is his story, told in Ward’s own words.

“Another was so unfortunate as to be obliged to travel in the winter. I met him at a ferry on the Niagara River, crossing from Niagara, on the British side, to Youngstown, on the New York side. It was a bitterly cold day, the 11th of January, 1853. Crossing the river, it was so cold that icicles were formed upon my clothes, as the waves dashed the water into the ferry boat. It was difficult for the Rev. H. Wilson and myself-- we travelled together--to keep ourselves warm while driving; and my horses, at a most rapid rate, travelled twelve miles almost without sweating. That day, this poor fellow crossed that ferry with nothing upon his person but cotton clothing, and an oilcloth topcoat. Liberty was before him, and for it he could defy the frost. I had observed him, when I was in the office of the ferry, sitting not at, but all around, the stove; for he literally surrounded and covered it with his shivering legs and arms and trunk. And what delighted me was, everybody in the office seemed quite content that he should occupy what he had discovered and appropriated. I yielded my share without a word of complaint. There was not much of the stove, and we all let him enjoy what there was of it.

The ferryman was a bit of a wag--a noble, generous Yankee; who, when kind, like the Irish, are the most humane of men. Upon asking the fare of the ferry, I was told it was a shilling. Said I, "Must I pay now, or when I get on the other side?"

"Now, I guess, if you please."

"But suppose I go to the bottom, I lose the value of my shilling," I expostulated.

"So shall I lose mine, if you go to the bottom without paying in advance," was his cool reply.

I submitted, of course. When partly across, he said to me, "Stranger, you saw that 'ere black man near the stove in the office, didn't you?"

"Yes, I saw him, very near it, all around it--all over it, for that matter."

"Wall, if you can do anything for him, I would thank you, for he is really in need. He is a fugitive. I just now brought him across. I am sure he has nothing, for he had but fourpence to pay his ferry."

"But you charged me a shilling, and made me pay in advance."

"Yes, but I tell you what; when a darky comes to this ferry from slavery, I guess he'll get across, shilling or no shilling, money or no money."[1]

Knowing as I did that a Yankee's--a good Yankee's-- guess is equal to any other man's oath, I could but believe him. He further told me, that sometimes, when they had money, fugitives would give him five shillings for putting them across the ferry which divided what they call Egypt from Canaan. In one case a fugitive insisted upon his taking twenty-four times the regular fare. Upon the ferryman's refusing, the Negro conquered by saying, "Keep it, then, as a fund to pay the ferriage of fugitives who cannot pay for themselves."

Samuel Ringgold Ward, Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro: His Anti-Slavery Labours in the United States, Canada, & England (London: John Snow, 1855), 173-. docsouth.unc.edu/neh/wards/menu.html.

Note: A shilling was British money. Twelve pence made one shilling.

[1] This is an old and offensive term for an African American, used here only because of the authentic context of this historical document written by Reverend Samuel Ringgold Ward.